Industry weights in US and UK market in 1900 and 2017Diversification reduces the exposure to any one particular distinct asset or risk. For the equity portion of the portfolio this can mean spreading investments across the world, diversifying by sector and buying shares in a lot of companies. That’s why low cost funds tracking broad market indexes are considered as a good long-term diversification instrument for an equity portfolio. Another reason for broad market diversification is the questionable ability of the individual investor to select winners or to avoid losers (nearly impossible tasks according to academic research). It is not only hard but also expensive (time spent on research and analysis and cost of access to data and research) to predict the future of the individual companies.

Although diversification is the key benefit of investing in those funds, there are also some obvious disadvantages. One of them are transaction fees and brokerage commissions due to a higher turnover; another are liquidity concerns related to larger and larger pools of assets tracking the same benchmarks and having a similar rebalancing schedule. These are widely recognized pitfalls, but I want to focus on the other important consideration, which is rarely mentioned but which is critical when constructing a portfolio – ‘Opportunity Cost’.

Classic broad index diversification sometimes called a ‘Core Exposure’ has a significant ‘Opportunity Cost’. This opportunity cost is related to the passive nature of the Classic Broad Index which deploys capital to a cap-weighted mix of all available, publicly traded companies. This passive allocation has a ‘quasi-static’ nature as it is based on the ‘market cap at that time’ without any short or long-term consideration related to sector or the business model of the underlying companies. Although according to the Efficient Market Theory, all future expectations are baked into price, some may argue that they are able to point out certain sectors or industries which would have more or less significance to the economy in the future.

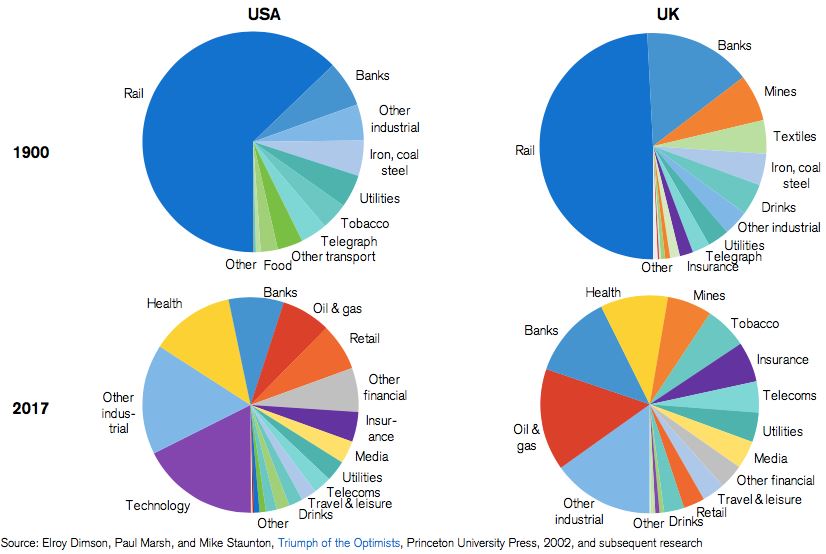

Over the decades industrial and technological innovations and revolutions have shifted the investor attention and market valuations to new sectors at the expense of declining industries. Century ago, more than 80 percent of the value of the listed companies were in sectors that are now very small or even extinct – examples include textiles, iron, coal and steel and most importantly rail roads which represented 63% of the US Market Cap in 1900, and now account for less than 1%. Innovation also created new industries such as car manufacturing, telecommunications, airlines or significantly grew the others. Today’s biggest industries – technology, healthcare, oil and gas were insignificant a century ago.

Based on the historical changes presented above, we can make an argument that the broad market index comprises many industries, some of which will gain importance in the future and some of which will decline. Avoiding declining industries in our portfolio and overweighting thriving industries of the future might improve returns and reduce the risk. This is also an opportunity cost of the portfolio invested in a broad market index.

As mentioned earlier it is difficult and costly to select individual securities; but one can argue that it would be easier to identify industries where companies have more room to grow and where external forces provide a tailwind for companies to prosper. One can argue that fields of robotics and artificial intelligence are examples of industries which will enjoy the above average growth in near future.

On the flip side we can try to identify industries where various external factors, including Environmental, Social and Governmental (ESG) became an additional burden, which increases resistance to the company’s operations. Coal mining industry is the industry which bears those adverse impacts.

To summarise, a broad market index comprises all industries, including the declining ones, which can be seen as the value traps. It also has relatively small exposure to the industries which have potential to become the main drivers of economic growth in the future, but haven’t hit the stage of the accelerated growth yet. We can invest passive in a broadly diversified ‘quasi-static’ portfolio whose allocation will slowly drift according to the market-cap changes and rebalances. But this exhibits the opportunity cost of not taking advantage of strong secular trends and also exposing to hidden risk of allocating capital to the value traps of the declining industries.